Lots of us play video games. In fact, the number of people playing video games only seems to increase -- the number of consoles in American homes exploded in 2007, rising more than 18 percent [source: Cheng]. If you've played video games before, you may have wondered what goes into making them. You may even want to get into the business yourself. Here are some of the questions that you may be wondering about:

Where do game ideas come from?

Advertisement

- How many people are involved in making a game and what do they do?

- How is a game developed?

- How does a game get to my local store?

The video game industry, like most technology, moves quickly and rarely looks back. It seems like every few years brings a fresh new batch of video game consoles, each vying for a place at the top of every gamers' heart. And over the years, gaming has become enormously popular all over the world, bringing in more than $1 billion in revenue and even surpassing the music industry in retail sales [source: Fritz].

To understand the entire process of video game development, we went to the folks at The 3DO Company. Also known as simply 3DO, the company was both a console developer and a third-party publisher of video games, with several titles for the Nintendo 64 and other game consoles, as well as PC and Mac computer systems. 3DO was founded in 1991 and released the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer (also known as simply the 3DO) in 1993. After poor sales and reception, the company dropped the console and shifted focus to developing video games (similar to what Sega currently does for the Nintendo Wii). 3DO declared bankruptcy in 2003, however, and no longer makes video games.

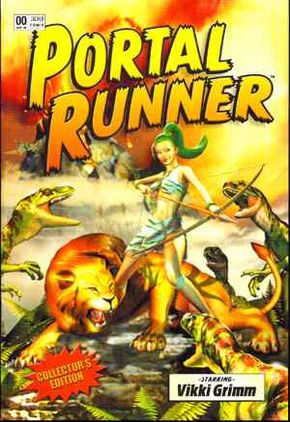

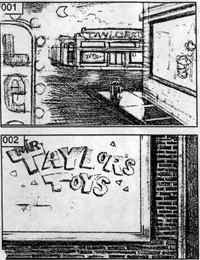

When 3DO was still around, we followed the development of Portal Runner, a game 3DO made for the Nintendo 64. In the process, we looked at the development of the game itself, as well as the process of getting a game off the ground and onto the shelves. On the next few pages, you'll learn about basic game technology, how an idea is developed and how a game is distributed.