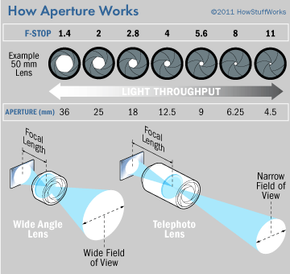

There are thousands of camera lenses on the consumer market. Every lens offers its own range of potential f-stop settings, which is critical to remember if you have an SLR (single-lens reflex) camera that lets you attach dozens or hundreds of different lenses. Each lens has its own maximum and minimum aperture setting.

Lenses are often marketed by their maximum aperture because the bigger the aperture is, the more useful the lens will be, especially in low-light situations. For example, a lens that can open up to f/1.4 is considered fast because it lets in a lot of light, allowing photographers to use faster shutter speeds to take sharp photos, even in dark environments.

Fast lenses are often complicated to manufacture and, as a result, they are usually more expensive than slower lenses. Lenses as fast as f/1.4 aren't uncommon, but you'll rarely see them with f-stops as large as f/1.0. However, these kinds of ultra-fast lenses do exist, such as Leica's 50mm f/0.95, which costs around $11,000.

Regardless of the type of lens, modern cameras make changing the aperture size very easy. Most models are equipped with both a manual (M) or aperture priority (Av, for aperture value) mode. Manual mode lets you control shutter speed and aperture independently. In Av mode, you pick a desired f-stop, and the camera automatically and continuously changes the shutter speed to maintain an even exposure.

Light levels will affect your choice of f-stop. In very bright light, you can use just about any f-stop setting, because you're able to control exposure with shutter speed. But if you want to make crisp photos in low light, you'll have to use the widest aperture to let in as much light as possible. Otherwise, your pictures could be underexposed.

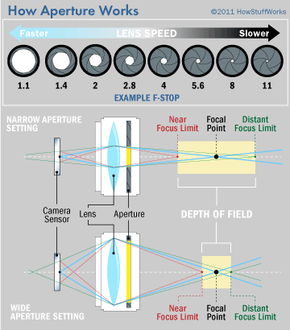

Aperture size affects more than exposure; it also impacts depth of field. In short, depth of field refers to how much of an image is in focus. When only one part of an image is sharp — for instance, a single petal on a full flower blossom — photographers say that the picture has a shallow depth of field. Alternately, deep depth of field is obvious in a sweeping, broad landscape, in which the flowery foreground and mountainous background are all relatively crisp.

Lenses with wide maximum apertures, such as f/1.4, are great for shallow depth of field. You can isolate one part of a subject, keeping it in focus while blurring the rest of the image. Many photographers use this technique to great artistic effect.