Imagine it's the night before patch day. You've parked your level-70 character, decked out in epic gear, outside what will soon be the forest ruins of Zul'Aman. Right now, it's just rocky pavilion with huge, wooden gates you can't open. But tomorrow, it will become the entrance to a dungeon full of trolls. You and nine of your friends hope to be the first players on your server to go inside.

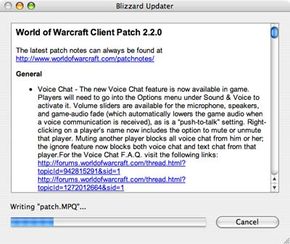

It's a risky proposition -- and not just because Zul'Aman is full of enemies that are far more powerful than you are. Zul'Aman is an addition to the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) "World of Warcraft," or WoW. As anyone who plays the game can tell you, making additions or changes to such an immense, dynamic world can cause some problems. On patch day, players often experience everything from server instability to problems with their user interface (UI) and addons. Players did get into Zul'Aman the day its patch went live, but only after the servers were down for hours of extended maintenance. And that didn't quite rival hours of downtime spread across two days just before the launch of the most recent "World of Warcraft" expansion, "Wrath of the Lich King."

Advertisement

Patch-day technical difficulties and the joy of exploring a new dungeon both come from the same basic source -- the enormous collision of people and data. The game worlds of Azeroth and Outland include 60 regions spread out across four continents. Each region has its own landscape and inhabitants -- both friendly and unfriendly -- and sometimes its own weather. Then there are representations of players' characters and everything they wear, carry and use. You can boil all of this down to ones and zeros stored on computer hard drives.

Players interact with all this data using their computers and an Internet connection. The players' computers store some of the data, and a remote server provides the rest. As one player interacts with the world, the world changes for other players -- the movement of data back and forth between the computer and the server allows this to happen.

Multiply this information by the thousands of players who can log on to a particular server at the same time, and the amount of traveling data becomes staggering. All the people playing the game also have the potential to make unpredictable decisions, making the exact interactions between players and the game hard to predict. When you think about the game in terms of so much traveling data, it's not surprising that patches and updates can have far-reaching effects.

In this article, we'll look at what it takes for data to become an interactive, persistent game world. We'll also explore the game's architecture and the people it takes to keep the game running. We'll begin with the human factor -- the people who play "World of Warcraft" and why they play it.

Advertisement