In National Lampoon's "European Vacation," Clark W. Griswold travels to the Old Country with Helen, Rusty, Audrey -- and his handy foreign language translator. The wife and kids make Clark look like a boob from time to time, but none set him up for ridicule like his trusty electronic device. When the "Pig in a Poke" grand-prize winner brandishes the translator at a French café, his Midwest-accented French earns him a barrage of indecipherable insults from the smiling, caustic waiter.

Back in 1985, it was hard to tell what was funnier -- Chevy Chase or the concept of a language translator that could actually perform well. That's because machine translation, the use of computers to translate from one language to another, hadn't lived up to the hype generated in the 1950s and '60s.

Advertisement

Here's a quick recap: After Georgetown University and IBM developed a machine capable of translating 60 sentences from Russian to English in 1954, scientists predicted that computers would perform near-perfect translation within five years. Not quite. Developing algorithms that could accurately translate foreign languages proved to be enormously challenging. In 1966, in a symbolic shrug of defeat, the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee reported that humans could perform faster, more accurate translation at half the cost. (Score one for the humans.)

Then a breakthrough. In the 1980s, computer scientists devised a way to make translations using statistical probability instead of complex rules based on syntax, grammar and semantics. They directed computers to analyze translated texts to determine the probability that a word or phrase in one language matched a word or phrase in another. The problem? It was difficult to get enough raw material to make the calculations possible, like trying to base probabilities on five coin tosses versus 5 million tosses.

That final information barrier collapsed when the Internet was commercialized in the 1990s. Suddenly, huge amounts of bilingual text became available, making statistical machine translation both feasible and, because of the huge reservoir of data available to it, more accurate than traditional, rules-based methods of translation. When the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency began throwing money around to develop translators for military use, the momentum finally shifted, and hand-held translators moved from the realm of science fiction to reality.

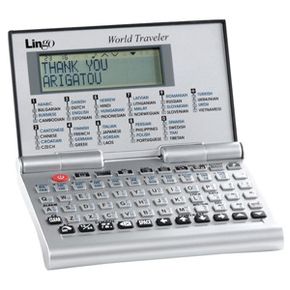

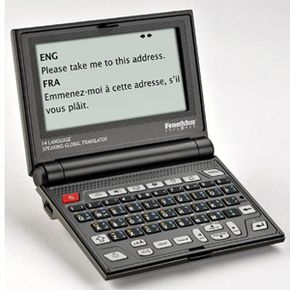

The hardware and software born from this R&D eventually trickled down into consumer electronics. Now companies like Franklin, ECTACO and Lingo feature a stunning -- and stupefying -- array of electronic translators. Before you rush to get yours, with dreams of speaking fluent Spanish as you stroll the streets of Madrid, keep reading.

Por favor.

Advertisement