Thanks to digital innovations, the Internet, tiny MP3 players and smartphones, we can choose to be awash in a sea of music, all day, every day. Indeed, if you came of age during the MP3 and YouTube revolution, you might find it hard to imagine not having nearly instantaneous access to every song ever recorded. But the concept of playing specific songs on demand all started with the jukebox.

In the early to mid-1900s, jukeboxes were literally the life of the party, in speakeasies and diners throughout the United States. Everyone wanted music, but radio didn't really suit every situation; broadcasts didn't let an audience immediately pick and choose the tunes necessary for working dance parties into a feverish pitch. Live bands were always an option, of course. But booking a band took time and money that a lot of establishments didn't have.

Advertisement

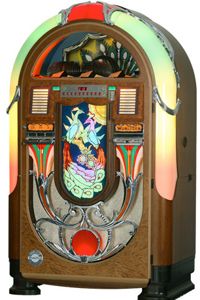

In this pre-iPod era, blasting a version of "In the Jailhouse Now" wasn't as simple as scrolling through a battery-powered device that fit in the palm of your hand. Instead of the glow of a tiny digital screen, people basked in the multi-colored glow of jukeboxes that measured in feet instead of centimeters. They didn't click furiously through a series of hierarchical sub-menus on a tiny silvery box; they leaned with their forearms resting on ornate wood, glass and steel cabinets to peruse a jukeboxes list of songs.

Like so many digital music toys today, the jukebox revolutionized music in terms of culture and technology. It's partly because of that revolution that so many people romanticize and yearn nostalgically for the days when a single music-playing machine could transform a drab, quiet tavern into a joyful (or sometimes mournful), magical place that filled ears and hearts with the power of music.

Keep reading and you'll see how jukeboxes emerged from old-school technologies and capitalized on societal changes, becoming one of the most recognized symbols of the 1950's.

Advertisement