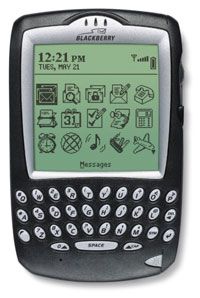

When the BlackBerry debuted in 1999, carrying one was a hallmark of powerful executives and savvy technophiles. People who purchased one either needed or wanted constant access to e-mail, a calendar and a phone. The BlackBerry's manufacturer, Research in Motion (RIM), reported only 25,000 subscribers in that first year. But since then, its popularity has skyrocketed.

In September 2005, RIM reported 3.65 million subscribers, and users describe being addicted to the devices. The BlackBerry has even brought new slang to the English language. There are words for flirting via BlackBerry (blirting), repetitive motion injuries from too much BlackBerry use (BlackBerry thumb) and unwisely using one's BlackBerry while intoxicated (drunk-Berrying). While some people credit the BlackBerry with letting them get out of the office and spend time with friends and family, others accuse them of allowing work to infiltrate every moment of free time.

Advertisement

In this article, we'll examine the "push" technology at the center of the device's popularity, RIM's former dispute with patent holder NTP Incorporated and its current dispute with Visto Corporation. We'll also explore BlackBerry hardware and software.

"Push" Technology

A PDA does a lot of the same things a BlackBerry does, and the PDA made its

debut several years before the BlackBerry. But until recently, the only way to make the information on most PDAs match the

information on a person's computer was to automatically or manually sync the PDA. This could be time-consuming and inconvenient. It could also lead to exactly the conflicts that having a PDA is supposed to prevent. For example, a manager might schedule a meeting on the PDA, not knowing that an assistant had just scheduled a meeting for the same time on a networked calendar.

A BlackBerry, on the other hand, does everything a PDA can do, and it syncs itself continually through push technology. BlackBerry Enterprise Server or Desktop Redirector software "pushes," or redirects, new e-mail, calendar updates, documents and other data straight to the user over the Internet and the cell phone network.

First, the software senses that a new message has arrived or the data has changed. Then, it compresses, packages and redirects the information to the handheld unit. The server uses hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) and transmission control protocol (TCP) to communicate with the handhelds. It also encrypts the data with triple data encryption standard (DES) or advanced encryption standard (AES).

The software determines the capabilities of the BlackBerry and lets people establish criteria for the information they want to have delivered. The criteria can include message type and size, specific senders and updates to specific programs or databases.

Once all of the parameters have been set, the software waits for updated content. When a new message or other data arrives, the software formats the information for transmission to and display on the BlackBerry. It packages e-mail messages into a kind of electronic envelope so the user can decide whether to open or retrieve the rest of the message.

The BlackBerry listens for new information and notifies the user when it arrives by vibrating, changing an icon on the screen or turning on a light. The BlackBerry does not poll the server to look for updates. It simply waits for the update to arrive and notifies the user when it does. With e-mail, a copy of each message also goes to the user's inbox on the computer, but the e-mail client can mark the message as read once the user reads it on the BlackBerry.

People describe BlackBerry use as an addiction, and this is why. Not only do they give people constant access to their phones, they also provide continual updates to e-mail, calendars and other tools.

Lately, RIM had been dealing with issues of patent infringement. We'll look at that next.

Advertisement