No one alive today can rightly say when early man first began telling time using the sun, moon, stars and other celestial objects. In the modern world, using these heavenly bodies for more than astrology may seem archaic, but keep in mind, much of today's calendar and timekeeping traditions have strong roots in ancient models. Back then, civilizations needed time as a matter of basic survival. For example, activities like crop planting and harvesting made it imperative to have knowledge of seasonal changes.

The first rudimentary methods of telling time involved simple observations of the natural world, perhaps by wedging sticks in the ground and monitoring the movements of the shadows. This particular experiment would have evoked the most fundamental part of a sundial, the gnomon (pronounced nom-on), which is the component that casts the shadow. It's easy to imagine this practice advancing into the use of obelisks, pillars and other megalithic clocks and calendars. Although some of these monuments can be considered sundials, it's the small, often portable, sundial devices of the ancients that we'll be learning about in this article.

Advertisement

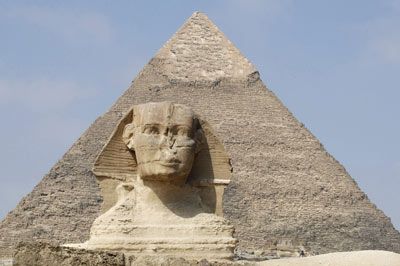

Ancient Egyptians are credited with the invention of sundials. Although obelisks were built as far back as 3500 B.C., perhaps the earliest portable sundial that has survived, often referred to as an Egyptian shadow clock, became popular around 1500 B.C. T-shaped or L-shaped with a raised end bar, these shadow clocks measured the morning hours as the sun swept overhead. Then, they were turned around to count down the afternoon.

It's important to keep in mind that the Egyptians weren't developing methods for timekeeping in a void. The practice of studying the passage of time -- whether minutes, hours, days, seasons, years or much longer -- was a passion of several ancient civilizations. Many of them were astoundingly accurate. The Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Mayans, Greeks and Chinese all devised clocks and calendars that reflect our current numerical model in a variety of aspects.

On the next page, we'll dive into why seemingly simple sundials can be a bit complex.

Advertisement