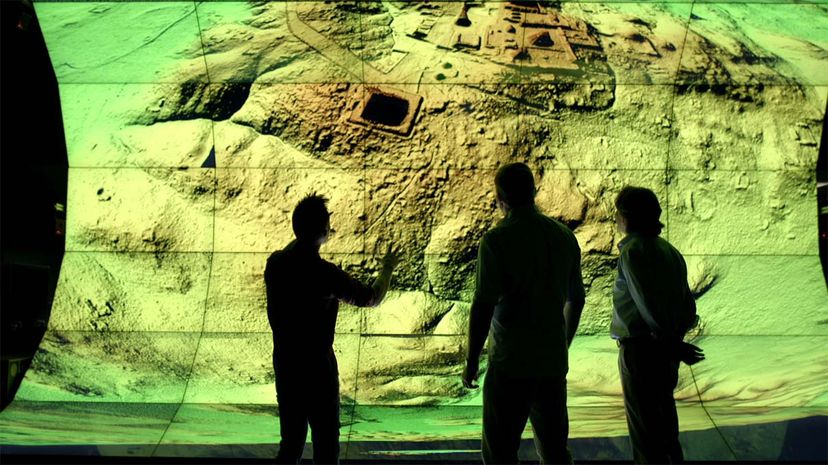

By using a technology called LiDAR to peer through the dense tree canopy of the Guatemalan jungle from above, researchers have uncovered a massive network of ancient Mayan ruins, which have been hidden for centuries.

The discovery, first reported by National Geographic, promises to alter our understanding of the Maya civilization, by revealing that it was far bigger in scale and more advanced and complex than previously believed. Researchers located the ruins of more than 60,000 houses, palaces, highways and other manmade features, according to the publication. A press release by the University of Houston, home of the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM), describes the find as sprawling over an area of 811 square miles (2,100 square kilometers). To appreciate the size of the Maya megalopolis, consider this: It was 1.7 times bigger than the modern-day city of Los Angeles.

Advertisement

According to National Geographic, the discovery suggests that the Maya civilization, which peaked 1,200 years ago, was highly sophisticated. CNN reported that the findings include a 90-foot (27-meter) tall pyramid, as well as evidence of agriculture, quarries and fortifications, plus an extensive road system that connected settlements. According to CNN, researchers believe that 10 million people lived in the region, many times more than previous estimates.

"These findings are important because the data lay bare an entire civilization that has not been disrupted by modern development," says Thomas Garrison, a Maya archaeologist and assistant professor at Ithaca College who worked with other researchers on the PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative. PACUNAM is a Guatemalan nonprofit that focuses upon aiding scientific and archaeological research and efforts to preserve the Central American nation's cultural heritage.

"We don't just see the big sites," Garrison explains in an email. "Instead we're seeing all of the infrastructure that made the Maya civilization function. How they fed themselves, how they traveled, and how they defended themselves."

From the density of the settlement, "we now know that the ancient Maya were able to sustain a population in this region that was substantially greater than what exists in the present, and they did so for over 1,000 years," Garrison says.

Diane Davies, a British archaeologist and educator who specializes in the Maya, says the discovery of the extensive ruins could help challenge widely held assumptions about the Maya culture, such as the belief that challenges of living in the rainforest environment would have limited the population size.

"The Maya lived in this area for over 1,500 years in the millions," she writes in an email. "To live this long and at such high numbers suggests that they were not only highly efficient in their agricultural systems but also environmentally aware – that is they knew the limitations of the environment and sought to protect it."

The new findings add to existing evidence of the Maya civilization's advanced state, such as their writing system, mathematics and complex calendars. The Maya "had some of the largest temple-pyramids in the world, all built without metal tools, the wheel or pack animals," Davies says. "These are just a few of their achievements and why people need to re-evaluate the Maya."

Advertisement